Browse the full results of the Impact Rankings 2024

Participate in next year’s Impact Rankings

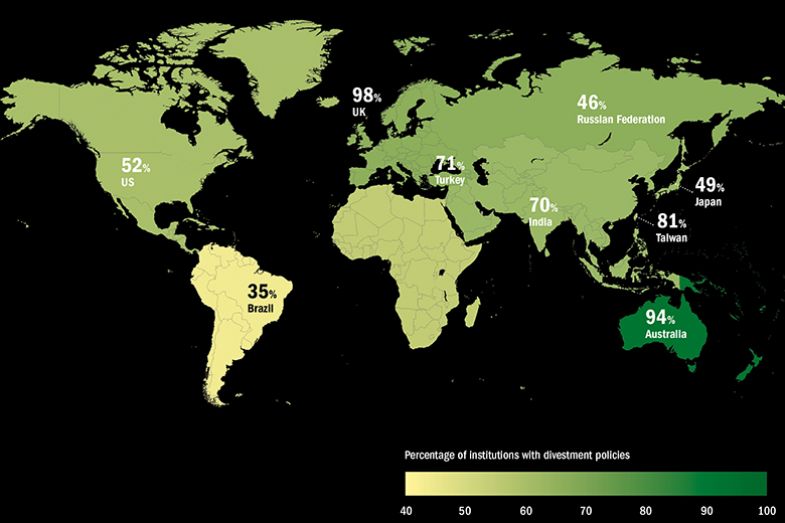

The proportion of global universities that have said they will divest from carbon-intensive energy companies is approaching two-thirds, a likely “tipping point” for the sector, but progress is more rapid in some regions than in others.

Data drawn from the Times Higher Education Impact Rankings 2024 indicate that 64 per cent of participating institutions reported having policies to withdraw from such investments, up from 44 per cent in 2020.

Some of the steepest increases have been seen in North America, where six in 10 universities now report having divestment policies, up from 31 per cent four years previously. A similar rate of growth, albeit from a lower base, is evident from data for the US alone, where the shift has been from 21 per cent to 52 per cent.

Rapid growth has also been reported across Asia, where 66 per cent of institutions now have policies on divestment, up from 42 per cent in 2020. In 2020, just 31 per cent of Indian participants had divestment policies, but that has now risen to 70 per cent, while the improvement in Japan has been from 13 per cent to 49 per cent. One of the strongest performers is Taiwan, where 81 per cent of institutions now have plans to divest, up from half four years ago.

Impact Rankings 2024: results announced

But these sectors continue to lag behind the strongest performers, primarily universities in Oceania, 91 per cent of which have divestment policies, including 94 per cent of Australian participants. They have been ahead of the curve since the launch of the Impact Rankings, which assesses universities’ performance against the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and which is led by Western Sydney University for the third year in a row. One metric measures whether a university has a policy on fossil fuel divestment, notably from coal and oil.

Taking the heat off: global divestment policies

The UK is among the strongest performers at country level, with 98 per cent of institutions reporting policies, up from 88 per cent in 2020. Across Europe as a whole, the proportion of universities with divestment plans has remained relatively stable, at 66 per cent, up from 62 per cent in 2020.

Universities volunteer to take part in the rankings and those that do so tend to be more committed to sustainability than others. So although it is not a representative sample, it gives an indication of the changing level of commitment to divestment since 2020.

The commitments within the policies vary. Some universities have little or nothing in their endowment funds and therefore no need for divestment policies; some have already divested their endowment funds; some have set goals aiming to divest all or some of their funds years or decades in the future; some commit only to divesting directly held investments; and some go further and commit to divesting indirectly held assets and from companies adjacent to the fossil fuel industry. For example, Aalborg University in Denmark, which ranks fourth overall in the Impact Rankings, does not invest in any coal, oil or gas companies, any firms where more than half of income comes from the supply of equipment and services to companies involved in fossil fuels, or any utility companies where more than half of the production is based on fossil fuels. By contrast, the University of Cambridge aims to divest from all direct and indirect investments in fossil fuels by 2030.

Student campaigners have largely fuelled the increase in commitments, along with pressure from academics and regulators.

“Schools in the US that publicly rejected divestment were most likely to cite their fiduciary duty – the concern that divestment would reduce returns to the endowments,” said Alexander Barron, associate professor of environmental science and policy at Smith College, who has researched higher education fossil fuel divestment. However, studies suggest that fossil fuel divestment does not have a negative impact on the long-term returns of a portfolio.

“Schools also frequently stated that they didn’t think divestment was an effective climate action, that they didn’t want to mix endowment strategy with a ‘political’ issue, or that they were focused on other sustainability actions,” Dr Barron added.

Evan Shenkin, assistant professor of sociology at Linfield University, said US universities had been slower to divest than their counterparts in other wealthy nations because “the power of the hydrocarbons industry to shape public opinion and ‘manufacture consent’ is somewhat more powerful in the US than in Europe”.

According to Dr Shenkin, current divestment campaigns in the US are based on earlier divestment campaigns against South African apartheid in the 1980s. “There was an international tipping point when the public caught on to the South African divestment movement. That is what I believe is happening now with fossil fuel divestment campaigns,” he said.

“There is also a sense of opinion management that many educational institutions are attempting to maintain to remain in good public standing.”

Other experts said universities in regions in which fossil fuel companies have bases tended to resist divesting because they were more likely to have donors from – and other connections to – fossil fuel companies.

Student campaigners in the US have started using legal action to encourage divestment. In April, student activists at Columbia University, Tulane University and the University of Virginia filed legal complaints over their institutions’ fossil fuel investments.

While the UK is one of the strongest performers in the THE ranking, student campaign organisation People & Planet suggests that about one in 10 British institutions with divestment policies applies a partial exclusion, usually meaning divestment from coal and tar sands, but not oil and gas companies. People & Planet’s own data suggest that a lower proportion of UK institutions, 72 per cent, have committed to divestment.

Laura Clayson, a campaigns manager at the network, said universities “should be fully divesting from fossil fuels in their entirety”.

“This is because the fossil fuel industry is both a leading contributor to the climate crisis and actively engaging in the oppression of those on the front lines of its extractive business model. The shapes these oppressions take are myriad but include the consistent undermining and violation of the rights of indigenous communities to free, prior and informed consent to proposed operations on their lands and self-determination, from Colombia to West Papua, Nigeria to Australia,” she said.

In nations where university divestment is more widespread, such as the UK, activists are turning their attention to other links between universities and the fossil fuel sector. These include research funding, links with intermediary companies such as banks and addressing the career pipeline from graduates to fossil fuel companies.

Swansea University recently became the largest university in the UK to commit to “fossil-free careers”, banning companies dealing in the extraction of oil, gas and tar sands from recruiting via its careers services.

Elsewhere, the proportion of African universities with divestment policies has increased from 30 per cent to 55 per cent over the past four years, and an even sharper rise was visible in South America, from 12 per cent to 43 per cent.

In less wealthy regions, fossil fuel divestment campaigners are coming up against beliefs that economic development should be prioritised, Dr Shenkin said. “One issue among Mexican divestment activists I ran into that was a barrier to divestment efforts in that country was the perception among some people that extracting and using hydrocarbons is a way to obtain national sovereignty and improve living conditions, and that environmental issues have to take the back seat,” he said.

Andrew Parfitt, vice-chancellor of the University of Technology Sydney, oversaw his institution’s divestment from fossil fuels. He told THE that the university initially tried to influence the organisation managing its investment portfolio to move away from the fossil fuel industry, but ultimately failed to do so. His advice to other universities in his position is to watch for signs that the fund is listening – or not. “When you cease to see the steps along the way, then you’re getting a clear signal that things are probably not going to change, or they’re not changing in the time frame that you want,” he said.