Several UK university departments, chiefly in the humanities, have recently either been closed or downsized. Philosophy, a historical staple of humanities faculties, is one of these – and there are reasons to support the claim that the subject has indeed run its course.

Martin Rees, the UK’s Astronomer Royal, had assigned the mystery of why anything exists to the “province of philosophers and theologians”. But Richard Dawkins, in The God Delusion, wondered “in what possible sense theologians can be said to have a province”. Indeed, he failed to see any good reason “to suppose that theology (as opposed to biblical history, literature, etc) is a subject at all”. I submit that much the same can be said of philosophy.

Once upon many centuries ago, philosophy and theology were scarcely distinguishable from each other. Their prolonged divorce proceedings were made more urgent when “natural philosophy” gave way to “science”; only then did philosophy begin to resemble its modern incarnation. Immanuel Kant was appointed to the chair of logic and metaphysics at Kӧnigsberg, in 1770, but he taught mathematics, physics and other subjects besides. T. H. Green, at Oxford, in 1878, was the first English professor of philosophy who was not obliged to sign up to the 39 articles of the Church of England. Philosophy as an academic “subject” is younger than, perhaps, most people think.

Even then, the divorce was not complete. Philosophers still suppose their claims to be applicable universally, as theologians do; for example, there is no more damnable “ism” to the moral philosopher than postmodern relativism. Both disciplines still tend to divide reality, or our perception of it, into just two discrete categories: so, where the theologian speaks of the sacred and profane, faith and reason, or soul and body, philosophers speak of free will and determinism, rationalism and empiricism and necessity and contingency.

Philosophers are also as exercised as theologians by the nature of Truth (with a capital T): both have thought of it as “out there” (or “up there”, as theologians once did). Perhaps this shared interest in Truth is a consequence of the disabling want of facts in both disciplines. Philosophers have little to do but to cast about for puzzles to ponder from their fabled armchair. Look up the subject in course prospectuses and book introductions and you will see the question “What is philosophy?” frequently asked. Is there any other academic subject that needs to ask itself what it is and what it does?

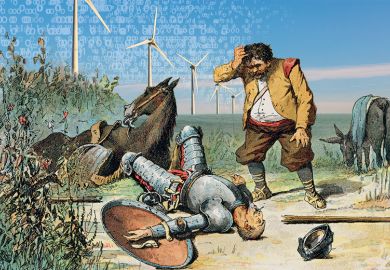

Philosophers continue to be preoccupied with what there is (metaphysics), and with what and how we know (epistemology). But science ought long since to have disposed of both pursuits. Jacob Bronowski, in his 1973 television series and book, The Ascent of Man, tells us that, in the early 1800s, the German mathematician and physicist Carl Gauss was “bitter about philosophers who claimed that they had a road to knowledge more perfect than observation”. More recently, Stephen Hawking scoffed that it was now science that bore “the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge”, not philosophy.

I once thought that ethics might justly survive as a focus of philosophising, just as I once thought that Sermon-on-the-Mount morals might be the most valuable heirlooms of religious belief. What, though, have all the books and taught courses on ethics added to the Golden Rule, in any of its versions: treat others as you would have them treat you?

It is surely not to ape Gradgrind, nor to dismiss the virtue of learning rigorous habits of thinking, to ask whether a subject can do without a corpus of factual knowledge altogether and still expect students to study it, at considerable expense to themselves and their universities.

It is a mark of philosophers’ own dissatisfaction with their subjects’ traditional content, that they have written books and introduced courses on ecological, medical, sporting and other themes that could well have been written by ecologists, physicians and sports writers. What, then, is the difference between one who philosophises and one who thinks? Do we not all philosophise? What transferable skills, what specialist tools, do those who call themselves philosophers have that might lead to breakthroughs of the sort that, in other subjects, win a Nobel Prize, Fields Medal, or indeed, Breakthrough Prizes? Linguistic analysis will not cut the mustard; logic will not butter parsnips; and philosophers have no monopoly on reasoning.

I am far from advocating that we replace philosophy departments with departments of thinking, or, indeed, critical thinking; one might hope, after all, that no subject ignores the need to think critically. Just as religious studies can claim to be a valid heir of theology, so philosophy might live on in a history of ideas (or, indeed, humanities) department. But such a history would include thinkers such as Darwin, Freud and Orwell, whom nobody calls philosophers, while many a so-called philosopher might not survive the cull.

Knowledge is not everything, but few will agree that philosophy has yielded knowledge, or skills of a sort that can compare with the fruits of most other university and college subjects.

Colin Swatridge has been a visiting lecturer at several central European universities. He is author of The Oxford Guide to Effective Argument and Critical Thinking (OUP, 2014) and Foolosophy? Think Again, Sophie: Ten reasons for not taking Philosophy too seriously (ibidem Press, 2023).

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login