Students appear to have shrugged off many of UK universities’ current challenges, with satisfaction with courses on the rise, according to a major survey of undergraduates.

Perceptions of value for money increased in the 2024 Student Academic Experience Survey, as did satisfaction with contact hours and ratings of teaching and assessments, despite a backdrop of job cuts, industrial action and talk of “rip-off degrees” by politicians.

In many cases it was international students who drove such rises, apparently largely unperturbed by higher tuition fees and the often-vicious debate about whether there are too many of them in the country.

The latest iteration of the survey – which has run for 18 years – represents “robust evidence” that “so many great things are happening” in the sector, said Jonathan Neves, head of business intelligence and surveys at Advance HE, and one of the authors of the report.

He said it showed the “resilience” of students and their institutions that universities were able to continue to offer a positive experience in the face of several challenges.

“We are getting all of this negative rhetoric which suggests there is something deeply wrong with universities,” said Josh Freeman, policy manager at the Higher Education Policy Institute (Hepi) and another author of the report. “Clearly, at least from these results, that doesn’t seem to be the case.”

“We can go on rumours and the cases that seem to be prominent. But, when you look at the overall impact, what students are telling us is quite a different situation.”

The survey finds:

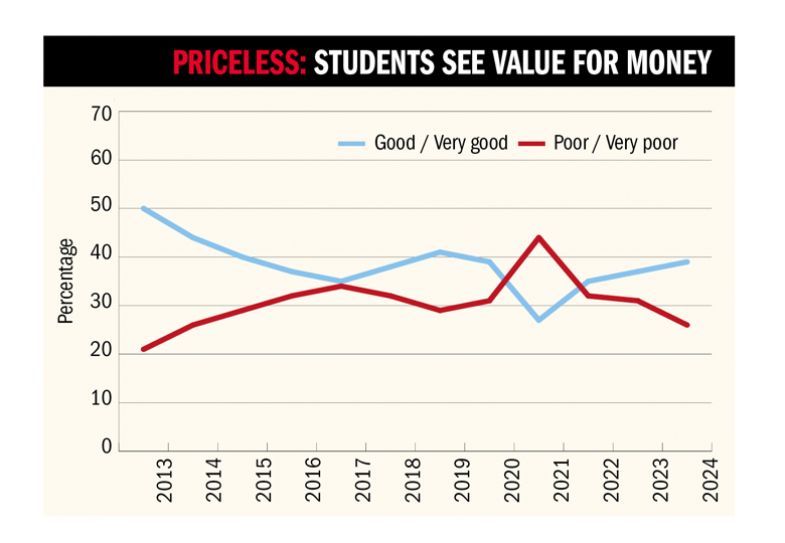

- Thirty-nine per cent of students polled felt their experience was “good” or “very good” value – up from 37 per cent in 2023. For international students, it was 45 per cent

- The proportion who felt their experience was “poor” or “very poor” value for money fell from 31 per cent to 26 per cent

- The proportion considering leaving their courses has declined significantly, by 3 percentage points to 25 per cent, and down from a high of 30 per cent at the end of the pandemic

- Sixty-nine per cent of students continue to have some lectures online, down from a peak of 90 per cent in 2022

- Sixty-two per cent of students say they use artificial intelligence in their studies, with older students and those from overseas more likely to use it more frequently.

Last year’s marking boycott – which disrupted end-of-year exams for thousands of students – did not appear to have an impact, with more students rating assessment feedback as more useful and timely than the year before.

The cost-of-living crisis continues to pose challenges, however, with the number of hours spent in paid employment each week increasing again to an average of 8.2, nearly double the 4.6 hours recorded in 2021. This rises to 14.5 hours when students who do not work are removed.

Even students on degree apprenticeships – who are paid while they study – reported having to take on additional part-time work because of the low salary these positions attract.

Rose Stephenson, director of policy and advocacy at Hepi, said the findings raised questions for an incoming government about the apprenticeship system as well as reinforcing the need to look again at maintenance support.

Campus resource: How to systematically improve your teaching using student feedback

For universities, she added, the challenges posed a risk to their model that, if unaddressed, could reduce the number of students going to university and increase dropouts.

“There are good arguments for having a different model, but that should be a purposeful, strategic decision to offer more flexible learning, which we might see anyway with the lifelong learning entitlement,” she said.

“At the minute, it feels a bit like that might happen accidentally because students can’t afford to do the traditional model of being at university. We need to have our eyes wide open to that as a risk.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login